Polarization is a fact of life. Not polarization in the scientific sense, but the kind where people pick one side of an issue and dig in their heels. In times of crisis, though, like the COVID-19 world we’re all learning to navigate, it’s nice to have general agreement on core issues.

One thing we all agree on is that LEDs have come a long way in a relatively short period of time.

“To be honest, the first LEDs that were out there, they were shit,” said Markus Klüsener, global product line manager at Martin Lighting. “I mean, they were really, really, shit. You wouldn’t even want to light up your garage with one.”

But today the technology has matured to the point at which virtually any lighting device that used to run on halogen or discharge can be replaced with LED.

[The Latest in Office Lighting]

“If you bought an LED at Home Depot, the first range was kind of blah and greenish, the dimming was terrible and everything looked kind of sickly,” said Matthias Hinrichs, product manager, Elation Professional. “In five years, that technology turned from so-so to replacing almost everything out there. We only benefit from that on the stage lighting side.”

Fred Mikeska, vice president of sales for A.C. Lighting, a supplier of multiple brands and product lines to the North American market, said stage lighting fixtures that combine efficiency, versatility, and reliability are enjoying demand as high as they ever have.

“There are so many benefits to choosing LED fixtures for lighting applications,” he noted. “In addition to the obvious savings in electricity, infrastructure savings can be substantial as LED systems allow for smaller mains power and HVAC systems when the facility is designed from the ground up around an LED-based lighting system.”

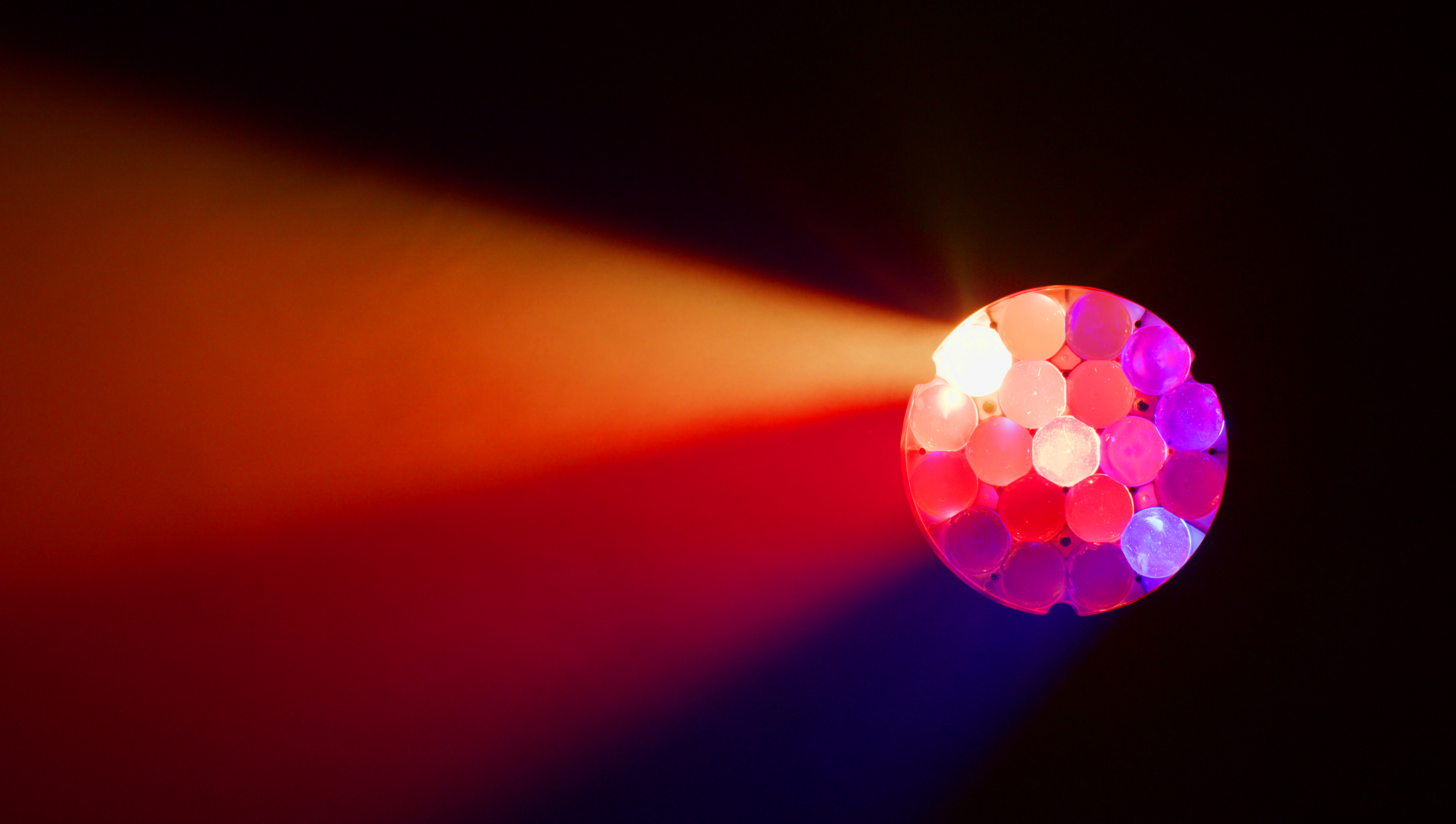

One of the developments Elation Professional has integrated into its stage lighting portfolio is multicolor LED engines such as the kind used in its Fuze family of pendants, spots, and framing lights.

“We used to have multi-engines [with] all individual lenses [and] some optics on there to handle it,” said Hinrichs. “Now you actually have very tiny engines instead of the color-mixing elements. Color mixing all happens in the engine. You eliminate a lot of stuff and the fixtures can get incredibly compact.”

In the installation market, Hinrichs noted, being able to offer a product that will reduce maintenance and downtime is a big deal. By eliminating the mechanical elements typically needed to fade color—several motors, glass, and the parts that make them work in concert—you remove a lot of variables from the equation.

“The color mixing quality is phenomenal on these,” he added. “The color rendering is really high, so they’re very well suited for key lighting for illuminating people and objects, which is something you do a lot if you’re doing a church or theater.

Martin Lighting is merging lighting and video with its P3 Pixel Push Protocol technology, which has long been used in its video products. This fusion happens in real time in the P3 processor, so the lighting and video feeds from the consoles and servers are automatically synchronized. The tech not only eliminates the complications of manual sync, but it reduces stage and programming time to the push of a button.

“In most use cases, you have sort of a separated flow in terms of programming, designing, and outputting video versus lighting,” Klüsener said. “You will have a lighting guy who is controlling the lights, and you will have a video guy controlling the video with content.” They have to communicate on the dominant colors and themes, and then execute the timing together in order to achieve a cohesive, blended stage.

“It becomes very easy to have a common look and feel to the show without having to even think about ‘what color tint is the video now, and how do I need to adapt that fixture?’” he added. “Because it’s also dynamic.”

The Martin MAC Aura PXL product line uses this technology to create tight beams and wide wash fields for lighting designers working in the concert and nightclub market, as well as for television and corporate applications.

The team at Chroma-Q, one of the key brands in A.C. Lighting’s portfolio, is focusing on designing versatile fixtures that allow spaces to transform—from an entertainment environment to a broadcast-ready room, for example.

The Chroma-Q Color One 100X is a compact LED PAR with “a fully homogenized optic, which eliminates the color separation and shadows synonymous with LED lighting while providing a smooth, even beam,” said Mikeska.

“This allows the Color One to be used as traditional stage wash and front light in HD broadcast settings. The Color One’s RGBA LED engine provides a wide color range with deep blues, vibrant reds, and soft pastels, allowing the Color One to match any corporate color.”

Mikeska noted that the COVID-19 health crisis has led many businesses to embrace virtual and online models, including educational institutions and studios that have reconfigured to live HD streaming. The Color One, he said, has a “CRI of 93 that accurately renders skin tones on camera, and adjustable frequencies that go up to 6,000 Hz to avoid flicker and ensure superb performance on camera.”

The developments in LEDs and stage lighting technology in general over the last two decades have elevated the standards of quality and efficiency across the board, said Klüsener, raising the stakes for manufacturers that are continually looking for ways to differentiate themselves.

“Everybody has learned, so it’s really hard to find products that are non-usable,” he said. “And with budgets being tight, which is something we will see when we are leaving this COVID-19-related crisis, customers are going to be very price sensitive about where they’re going to spend their money.”

As for the next big thing, Klüsener points to laser-driven LEDs that produce every color at the same brightness, like those currently produced by Clay Paky, as a technology to watch.

“That is definitely going to intrigue lighting designers because there was always the problem of ‘Oh yeah, how bright is your mixed red, or your primary red?’” Klüsener said.

“That is definitely going to intrigue lighting designers because there was always the problem of ‘Oh yeah, how bright is your mixed red, or your primary red?’” Klüsener said.He added, however, “with laser engines, you have a lot of candela, you have a lot of high intensity, but you don’t have lumens. And if you want to spread a beam wide, you need lumens. So that’s the next step that will be requested by lighting designers and users—to make this kind of technology widely available and usable for wider-spread applications.”