When the core of your business is audio and visual, remember an inherent handicap: not everyone can hear or see perfectly. According to the most recent statistics, approximately 15 percent of American adults (37.5 million) aged 18 and over report hearing difficulties. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that 1.3 million people in the U.S. are legally blind.

These unfortunate statistics have long mattered to AV integrators whose installations must meet requirements set down by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the civil rights law first established in 1990 that prohibits discrimination based on disability. Increasingly, AV integrators are seeing the scope widen in an interesting way, with corporate clients requesting AV environments that are accessible to the hearing and vision impaired, even when not specifically required by the ADA.

There is frequently confusion between the ADA and its broader accessibility umbrella. “Accessibility is a generic term that refers to an environment where people with and without disabilities would be accommodated in activities such as getting into and out of a space or building, reaching objects and controls, and operating systems such as audiovisual systems,” said Timothy Cape, CTS-D, principal consultant for Technitect, a technology design and management consulting firm. “ADA Compliance is a term that refers to environments that adhere to the ADA laws and guidelines, providing ‘substantially equivalent or greater accessibility and usability.’

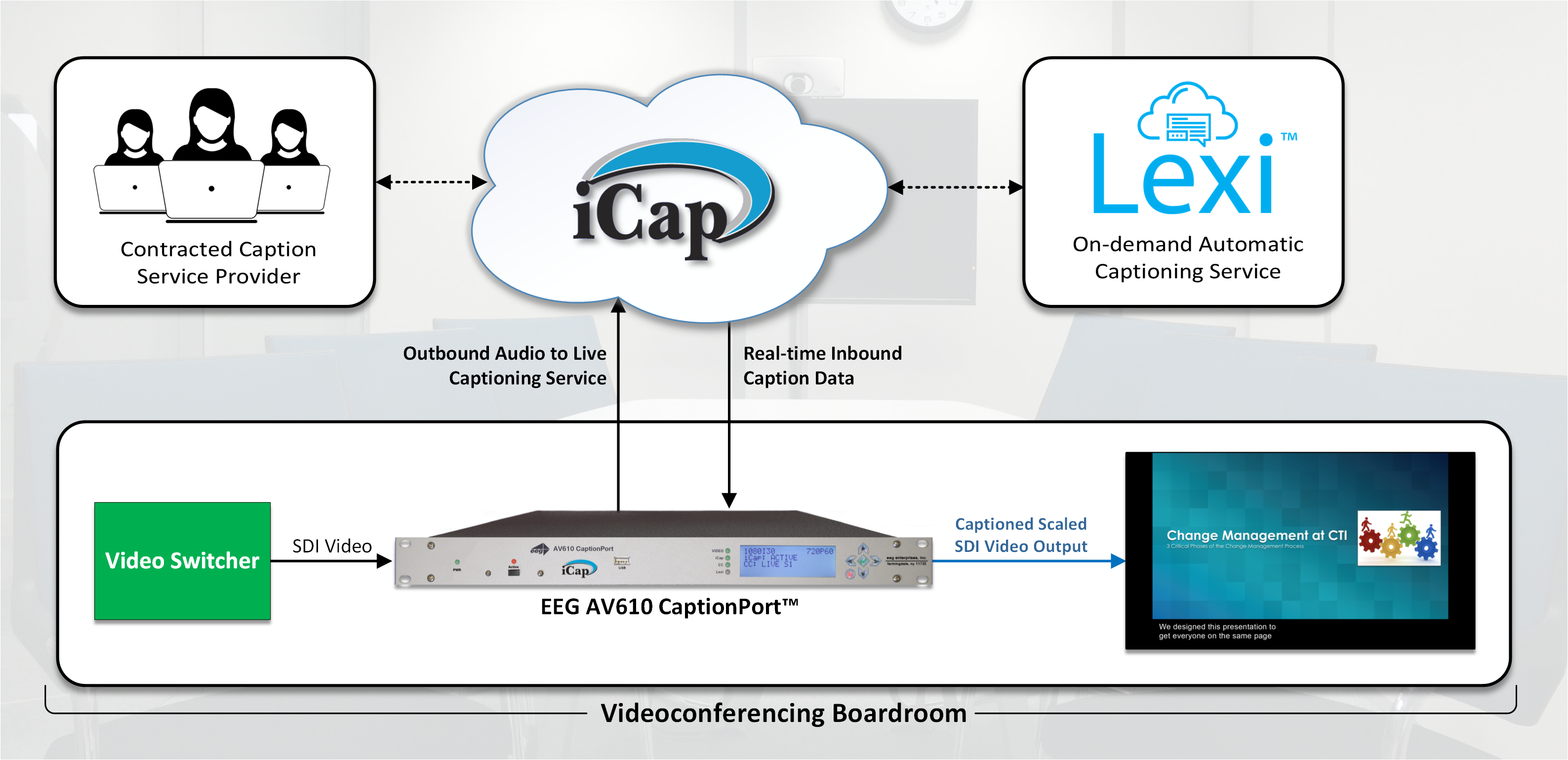

Understanding how to incorporate accessibility solutions for the hearing and vision impaired—such as assistive listening, audio description, and closed captioning—is proving to be helpful in behind-the-scenes corporate projects including boardrooms and videoconferencing. “Most major organizations are looking into accommodations now or have them already,” said Dave Watts, marketing manager for EEG, a closed captioning solutions provider. “Last year we helped a tech giant in Seattle deliver live captions to about 100 meeting rooms across five cities for a large corporate summit they had planned. The EEG encoders used for the project were virtual, which kept their costs down and also allowed them to implement the solution with very little lead time as there was no hardware to ship.

“The infrastructure for captioning can be more widely used now more than ever because of the recent emergence of inexpensive and relatively high-quality automatic speech recognition technology,” Watts continued. “Now professional transcriptionists can be used to cover high profile events, and automatic captioning can be used to fill in gaps when needed.”

Along with captioning of video, another solution for the hard of hearing are assistive listening devices (ALD), which are used to improve hearing ability for people who are in situations where they can’t distinguish speech from noise. The DURATEQ is a ruggedized handheld device from technology provider Softeq that is frequently used at major attractions and national parks, providing amplified audio via an FM transmitter, as well as the ability to connect with hearing aids.

Softeq’s DURATEQ can also be used to assist the visually impaired by connecting to audio description services, which augments experiences via live or recorded speech that describes the surrounding environment. “There are professional audio describers that go into a space and describe meaningful content to people who are not sighted,” said Paul Fruia, VP of engineering for Softeq. “In a museum, for example, they would describe the dimensions of the space, provide perspective on where things are located like exhibit locations and exits, and add details like, ‘the floor has a lush green shag carpet.’”

If a blind board member were in a meeting where there’s just vocalization, then there would not be a need for audio description. However, if there’s a presentation involving graphics or video, then there would be a need for that service in the boardroom. “There are two ways to approach that,” Fruia explained. “If it’s a PowerPoint presentation made by an employee, and there’s no audio description built into it, you would need an audio describer who can see and hear what’s going on—perhaps via video on a platform like Webex—and would speak into a microphone. The blind person who’s wearing the device would then hear that audio description in conjunction with the main program.”

“The other option is that if the audio visual program is professionally created, it could be a requirement that it includes the audio description track, as well as captioning. The film industry is starting to integrate this content more frequently onto separate channels, and large corporations are probably considering this as well for their marketing pieces,” Fruia predicted.

Providing captioning for a hearing-impaired board member could have multiple signal paths, as well. “All of our live AV accessibility solutions work by delivering an audio reference of the input video to a choice of a contracted human captioning service or to our automatic captioning service, Lexi, over a standard broadband connection—in real-time, these services return a text transcription of your audio over the very same connection,” said EEG’s Watts. “If the attendee is remote and the video is being streamed, the stream can be directed to our cloud-hosted caption encoding service, Falcon, simply by entering the provided ingest URL into your streaming media encoder settings. This will route the live RTMP stream to Falcon, which will handle the audio/caption exchange, then forwarding the fully captioned RTMP stream to the designated streaming service. Our Captioncast module also enables attendees to view the captions on personal devices, simply by visiting a unique URL which we create for each customer.”

As greater demand for accessibility continues to emerge on the corporate level, AV integrators who come in prepared stand to save the project time and money—while ensuring a full experience for all. “Knowledge of ADA design requirements, and the many exceptions, can make design of AV systems in compliance from the beginning of a project, rather than having to redesign and/or reinstall parts of the system during installation or after it is completed,” Cape pointed out. “Including ADA in the design process can also simply make a good impression on clients—both architects and owners—who are required to have these accommodations in their spaces. It helps system owners to comply with the law, and fulfill its intent, which is to remove barriers for people with disabilities, allowing for access and participation in events and services that might not have been possible otherwise.”