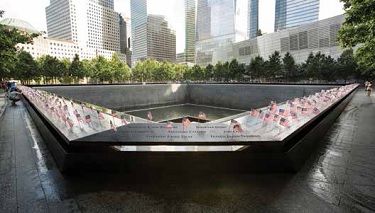

When people visit a museum of a historical event—of a Civil War battle, for example—they expect to be transported to that era by means of artifacts and period-costumed staff. But what about an event so close to the present, one that nearly every adult watched unfold live on television? The answer, of course, is absorbing audiovisual elements, and the National September 11 Memorial Museum has them in spades.

“Everyone remembers where they were and what they were doing that morning, and I think the audiovisual aspect of the museum really brings you back to that moment in time,” said Fernando Mora, the museum’s manager of audiovisual and multimedia technology. “You walk through those doors of the historical exhibition, you hear the 9-1-1 calls from the first responders, and you get a real sense of the initial confusion and chaos of the moment, followed by the panic after the second plane hits the South Tower, then the subsequent collapse of the towers. I believe audiovisual experience plays a large part in this effort without overshadowing the physical artifacts. I think the exhibit designers struck the perfect tone in this regard which is no easy task.”

Telling the Story

Located largely beneath the accompanying 9/11 Memorial in the foundations of the original World Trade Center towers in Lower Manhattan, the museum features some 150,000 square feet of exhibition space and more than 90 AV exhibits that add to its educational, experiential, and memorial functions. Designed by integration firm Electrosonic and opened in May of 2014, the AV operations have been fully under the care of the museum’s own team, led by Mora.

Since then, the AV team—which consists of Mora as manager/engineer, AV engineer Jose Vazquez and two technicians, Chris Fraley and Marc Thompson—are in charge of all day-to-day operations and internal upgrades.

“The vast majority of the AV projects are designed, engineered, and installed in house,” Mora said. “We very rarely go out to integrators for these projects. I have an integration background, and so does our engineer, Jose Vazquez."

This may seem like a tall task—even more so, considering that much of the AV equipment is due for a refresh, owing to an unforeseen setback that delayed the museum’s opening.

Projectors are a big part of the upgrade process, according to Mora. Of the museum’s 64 projectors, 24 have been replaced with Christie G Series laser-based models; of the others, 27 lamp-based Digital Projection models will be exchanged with laser units in 2018 saving us approximately $400,000 in lamp costs over the life of the projector. This is an important consideration, given the museum’s extensive hours of operation and inaccessibility of some of the units: in the cavernous Foundation Hall, for instance, three lamp-based projectors are mounted within the 60-foot-high ceiling, and lamp changes and maintenance necessitate bringing in a very large scissor lift.

Getting signals to all the exhibits around the sprawling facility isn’t easy either, and is another area ripe for enhancement in the coming years. On the audio side, Peavey MediaMatrix NION DSPs in the three control rooms use CobraNet for audio distribution; Mora said that the museum is in the midst of gradually moving this process to Dante. On the video side, Adtec SignEdje Watchout and 7th Sense players send signals via Extron transmitters and receivers via DVI-D.

“This is still a traditional AV system, but it has a lot of IT components to it,” Mora said. “Every device here has an IP address; I can get to anything remotely. Our network has five VLANs, but they’re mostly for control, monitoring and intersystem data communication. We’re putting small amounts of video on it, little by little, as we ramp up. The idea is to completely go AV over IP over the next three years.”

One way that Mora is selling the idea to upgrade to AV over IP to the museum’s budget decision makers is the “disaster recovery element,” as he calls it: the freedom from relying on so many physical devices that could be damaged in a future flooding event. “If one control room gets flooded, this entire wing of the museum is down, and we have to find a way to get system operational again quickly,” he said. “But if we were to go AV over IP, we are less reliant on where the sources originate from. We can take the show, bring it over another control room, and drive the content from there.”

However, Mora acknowledges this transition can’t be rushed: with as many as 90 individual exhibits and 120 video streams (accounting for blended exhibits) playing at once, the move to full IP requires patience. “Those are things you have to scale up for,” he said. “You have to buy the hardware, give your IT managers a chance to balance the load, and be able to handle it, or else all we’re doing is going from a stable system to an unstable system, and that’s not going to help.”

While audio and video presentations play a powerful part in telling the story of the events of 9/11, they are equally moving in aiding in the memorial aspect of the space. A central feature of the museum is the memorial exhibition. Lining four walls within the footprint of the original foundation of the World Trade Center South Tower are portraits of almost all of the nearly 3,000 people who lost their lives in the 2001 and 1993 attacks. Around that space are several ELO 3243L interactive touch display tables, where visitors can look up more information on each victim. Visitors can then choose to send a person’s profile into an interior room or what the museum calls “Inner Chamber” where their name and information are projected onto a screen and a recording of their name is played. There is also a wing featuring recording booths, where visitors can record testimonial videos about loved ones or their memories of the event.

In the atrium, there is an auditorium that, while normally functioning as a theater that screens films every 30 minutes over the course of the day, can also serve as a lecture hall and event space with sophisticated broadcasting abilities. Using a NewTek 460 video production switcher, the auditorium’s control room can pull from the space’s Sennheiser SKM5200-II wireless mics and three Sony BRC-H700 PTZ cameras, and broadcast out a streaming feed of the occasional large event, such as when Yankees’ erstwhile manager Joe Torre spoke about the importance of baseball in restoring normalcy to the city after the attack.

Maintaining the Message

Keeping a facility of this scale running smoothly would be a challenge for any size team; with just four technicians, the museum’s AV team certainly has its hands full. With a weekly operating schedule of nearly 80 hours and more than 11,000 visitors streaming through its exhibits on an average day, a lot can go wrong.

“Every day there are some exhibits that are problematic,” Mora said. “Ninety-five percent of our exhibits, if they’re having a particular technical issue, they happen in the morning: as PCs boot up, players start, or projectors turn on after being off overnight.”

Sometimes, a particular piece of equipment will require some clever troubleshooting. One of the touch-tables in the memorial exhibition area would have issues turning on, and Mora’s team eventually figured out it was the result of a problem with the hot-plug detection on those screens, so they changed the entire design of it. Several projectors in a film screening room would blow their lamps in the middle of the day; they discovered the cause was outdated firmware. The Macs capturing a visitor’s testimonial in the recording booths would frequently crash, so the team wrote a script that delayed the launch of the recording software one minute after booting up, exponentially reducing the incidence of failure.

Mora says the key to staying on top of maintenance for over 1000 devices is assiduous documentation. Using a database management system called Atlassian Jira, he keeps detailed reports on every issue in each exhibit. “[In the database,] the problems have a line of issues month by month, and it’ll show you right when we made a change, and how that affected the fault reporting,” he said.

Meticulous reporting also prevents small problems from persisting. “If there’s an audio wand that’s not working, one of the technicians fixes it I wouldn’t typically know about it,” Mora said. “But because I keep track of it in JIRA, I can tell how many times that one wand has failed, that allows me to provide resources to it, monetarily, or equipment wise, that helps resolve problems.”

All of these preventative and reactive measures have so far kept malfunctions mostly invisible to the public, allowing the audiovisual elements to meld with and enhance the transformative gravity of the space. Mora said he’s read many reviews of the museum on TripAdvisor extolling AV’s role in enriching the experience.

“I feel that in many ways we are the custodians of this incredible content; it’s a very important part of the museum, because of the time in which it happened,” he said. “We were in an audiovisual age at the time, and there were many cameras in the hands of the public, as opposed to something that happened during World War II where many events went undocumented, for example.”

But ultimately, Mora believes that AV—no matter how moving—is merely an instrument for conveying the solemnity of the space, and for retelling the events of a day that changed America forever. “I think that when people come here, they leave with a completely different perspective on what that day was,” he said. “For us, it’s not the audiovisual; it’s what’s being displayed here, and our job is to make sure the story is told clearly, that it looks good, sounds good, and we’ll let the story tell itself. The story is powerful enough; it’s not something that we need to add anything to.”