The legacy of The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound

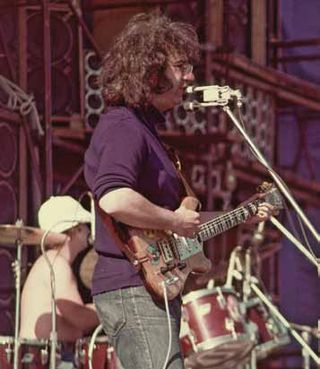

Weighing in at 75 tons in freight, the Wall of Sound (seen here on the 1974 tour stop in Vancouver) was comprised of 586 JBL loudspeakers and 54 Electro-Voice tweeters powered by 48 McIntosh 2300 amps. Like Woodstock, much of the buzz surrounding the Grateful Dead is part legend, part myth, and part reality. For one, everyone was “there,” even if only in their own minds. But one thing we can’t argue about is the Wall of Sound’s existence—and its influence on the professional audio industry. Looking back on what went into the construction of the thing, one has to ask: Were those guys on drugs?

Probably. Credited with the Wall of Sound’s conception, Owsley “Bear” Stanley was also the main supplier of LSD for the famous Acid Tests Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters hosted in the San Francisco Bay Area during the mid-60s. His interest in experimentation extended into live audio production, and while serving as the Dead’s tech, he, Dan Healy, Mark Raizene, as well as Ron Wickersham, Rick Turner, and John Curl of Alembic began working on a design that combined separate sound systems for each instrument, as well as vocals. This giant rig, comprised of JBL components, would tower behind the musicians—instantly raising questions about feedback. They handled this by applying a differential mic concept; by spacing two mic capsules an inch apart, any common signals that went into the both of them from the backline PA were canceled out. The musicians would sing into just one of the capsules, and that signal would be routed through the vocal portion of the PA .

Disastrous feedback was prevented by a differential mic setup, spacing two mic capsules an inch apart, canceling out any common signals from the backline PA.

The Wall of Sound has been dubbed the industry’s first line array, but according to Mark Gander, director of technology at JBL Professional and, and by all accounts the company’s resident archivist, the concept was inspired by the theory and calculations laid out in Acoustical Engineering by Harry F. Olson, a book originally published in the mid- ’50s. From there, it became a giant experiment. “There were all of these experiments with physically mounting the speakers, and it ultimately evolved into all of these vertical columns, and then, cylindrical segments for mids and highs and the vocal PA , or the piano PA ,” he explained. “There was a tremendous amount of experimentation based on acoustic principles and Olson, and the knowledge that these guys had from their backgrounds. But then, they were also putting this stuff up and taking it down every day, and saying, ‘Let’s try it a little bit differently this time.’”

During these experiments, Stanley also turned to Meyer Sound’s John Meyer, who was designing loudspeaker systems for McCune Sound Service at the time. Stanley relayed that the musicians were starting to complain that it was getting too loud on stage, and that the sound techs were having trouble achieving adequate coverage in balcony areas. Meyer proposed his JM3 and JM10 systems to solve coverage and stage spill issues, and thus began his relationship with the Grateful Dead, which continues today. (Meyer is still working with band members Bob Weir and Mickey Hart on their recent projects.) “Those relationships are important,” Meyer said, because they pushed product development at a time when there was more room for experimentation. “In all business, it’s easier to follow success rather than pioneer something new. There’s always risk of failure when you try something new. You can’t make promises because you don’t know.”

Wall of Sound creator Owsley “Bear” Stanley asked Meyer Sound co-founder John Meyer, who was designing loudspeaker systems for McCune Sound Service at the time, to solve coverage and stage spill issues. Meyer proposed his JM3 and JM10 systems, and thus began his relationship with the Grateful Dead, which continues today.

The Wall of Sound’s actual duration on the concert circuit was short: it officially debuted in 1974, and was retired a little over a year later. Much of this was because of sheer economics. It was extremely time-consuming to set up, and at one point, there were alternating crews leapfrogging one another: while the Dead performed one gig, there was another crew assembling the scaffolding at the next site. Not only was labor expensive, but the oil crisis was making it cost-prohibitive to truck the thing around.

Still, Gander believes that its legacy still touches the industry today. “It really was an antecedent for what touring uses almost exclusively these days, which is the line array concept,” he said. “The line array concept was very, very influential; even though it took many years for it to catch on, the Wall of Sound was very seminal and influential in people’s thinking.”

Or, as Meyer puts it: “It’s more timely than people think. It’s not just history.”

Carolyn Heinze is a freelance writer/ editor.