In 2012, Greg Bawden was serving his third term on the Seattle-area Riverview school district’s education board. Though he hoped to begin a fourth term in 2013, he had a problem. A few years prior, Bawden had begun to experience hearing loss. Even with hearing aids, he found it difficult to engage fully in board meetings. When plans emerged to create new office space, Bawden saw an opportunity. He recommended the district equip its new boardroom with an assistive listening system (ALS). Absent a solution, “I would have had to resign,” Bawden said, “because I can’t participate in meetings if I can’t hear everybody.”

At Bawden’s urging, the district installed a hearing loop (also known as a loop). Having tried both loops and more widely installed RF systems since becoming hard of hearing, Bawden finds loops offer a far better experience.

“What a huge difference when I’m in a looped environment as opposed to relying on, essentially, a walkie-talkie,” he said. “It’s such a relief to not be hearing the ambient noise and have the sound system delivered directly into my ears.”

IN THE LOOP

In its most basic form, a hearing loop (also known as an induction loop) consists of a current amplifier connected to a copper wire looped around a room. Audio is run through the amp and inducted onto the wire, creating a magnetic field that is then inductively coupled to a coil, called a telecoil or t-coil, in a listener’s hearing aid or Cochlear implant. What makes loops unique among ALS’s, and so popular in the hard-of-hearing community, is that they communicate directly with an individual’s own hearing aids or Cochlear implants. Those devices restore volume as well as frequencies users struggle to hear on their own, which means loops deliver custom-equalized audio directly to listeners’ ears.

Illustration by Kim Rosen

“Those highs and mid-highs are restored through the EQ process that the audiologist has set up,” said Mike Griffitt, corporate training manager at Utah’s Listen Technologies. With a loop, users “hear not only with added volume like with traditional ALS’s, but they also get that speech intelligibility.”

And because loops don’t require intermediary devices, they offer discretion. Whereas RF and IR require users to draw attention to themselves with headphones or bulky receivers, to connect to a loop system, users simply need to activate their devices’ telecoils.

Bawden is not alone in preferring loops. Hard-of-hearing psychologist David Myers launched the Let’s Loop America campaign back in 2001 in Holland, MI. There and in neighboring Zeeland, loops have been installed in scores of public venues—churches, theaters, event spaces, and schools—that traditionally feature amplified audio. More than 130 venues in Holland and Zeeland are looped, including several facilities at Hope College, where Myers is a professor. The Gerald Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids, MI, recently completed a second round of loop installations, adding coverage to its main atrium and meet-and-greet areas after a 2007 installation provided loops in the two concourses and gate waiting areas. In all, there are more than 700 looped facilities in Michigan, more than anywhere else in the country.

But while the rest of the nation has been slow to catch up, it seems the movement is finally gaining traction. Loop advocacy groups have sprung up all over the country, and the resulting increase in public awareness is delivering results. In New York City, Broadway’s Gershwin and Rodgers Theaters were recently looped, and loops have been installed at ticket booths in 488 subway stations. Loops have also been approved for New York City taxis after a successful 18-month pilot program.

Despite these and other high-profile installations, however, the total number of loops is tiny relative to the number of venues in which advocates hope to see them. ALDLocator.org lists just 1,812 looped venues nationwide (though that number is likely low because the site is self-reporting). As it turns out, the technology has existed since the Depression—inventor Joseph Poliakoff filed a patent for a loop system in the UK all the way back in 1937. Loop took root in Europe in the early 1970s, particularly in the UK and Scandinavia, and has been firmly established as a viable ALS there for years.

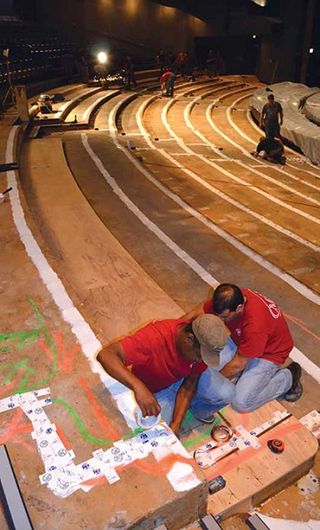

The team prepares to install a hearing loop system at the Gershwin Theater in New York City. One reason the loop has been slow to take hold in the U.S., said Cory Schaeffer, Listen co-founder and vice president of sales, is that the feature they require to work—telecoils—simply hasn’t been available here. In Europe, where nationalized healthcare is the rule, hard-of-hearing patients have easy access to hearing aids, and consequently telecoils, which became a standard feature in the ‘70s. In the U.S., not only are hearing aids generally not covered by health insurance plans, but telecoil-equipped hearing aids only recently became commonplace. Although today close to 80 percent of hearing aids in the U.S. have telecoils, Schaeffer said, as recently as 2001, the total was less than 40 percent.

Audiologists, meanwhile, may be just as unaware of loops as their patients. Greg Bawden said his first audiologist failed to set his telecoils up correctly, reversing the proper ratio of ambient sound to inducted sound. Sometimes, Schaeffer adds, audiologists simply don’t set up their patients’ telecoils because they don’t foresee an opportunity to use them.

“An audiologist might say, ‘Oh, we’re not going to activate it because there’s really no place you can use it,’” Schaeffer explained. “Well, then venues say, ‘We’re not going to put [a loop] in, because nobody’s asking for it.’ So it’s really on this cusp where it’s a chicken-or-egg thing.”

Compounding the awareness issue is the fact that in the past, loops often just didn’t work that well. Whether unscrupulous or well-intentioned, installers in prior decades sometimes just didn’t know what they were doing.

“Ten, twenty, thirty years ago,” Griffitt said, “here in the U.S., what people were doing was just using telephone wire wrapped around a room, hooking it up to any standard audio amplifier and telling people, ‘There’s your loop system.’” Among the few had heard of it, loop’s reputation “suffered drastically. It kind of got a black eye here.” Indeed, Schaeffer and her co-founder Russ Gentner, who is also Listen’s CEO and a hearing aid wearer, were among the skeptics. “We sold against this technology for most of this company’s [16 year] history,” Gentner noted.

The industry is changing, however. In recent years, advocacy groups have seen their work rewarded with an increase in media attention. At the same time, changes to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) implemented in 2012 strengthened the ALS mandate, removing the provision that only venues of a certain capacity needed to provide an ALS. Now, regardless of capacity, ALS’s must be provided “in each assembly area where audible communication is integral to the use of the space.” Not only that, but at least two of the receivers installed as part of that system must be hearing aid compatible.

Perhaps more significantly from a business perspective, the industry has grown up. Recognizing that loop had a less than sterling reputation in the U.S., distributors and manufacturers like Listen and Williams Sound entered the loop market via partnerships with major manufacturers in Europe. All of Listen’s loop gear is supplied by the British company Ampetronic, while Williams has a deal with German firm Humantechnik. Listen and Williams also both provide intensive training to their installers. Listen offers a selective two-level certification program to which installers must apply.

“We’re really handpicking certain AV integrators that we feel have the technical sense, and have design engineers that understand higher level systems,” Griffitt explained. Selectivity is essential, Gentner added, given that the growth of the market is dependent on awareness, which in turn requires successful installations. “We’ve really taken the time to teach the dealers and the consultants how to specify, how to design and install these systems so that they’re done right,” Gentner said. “We knew if we didn’t do that and we started getting systems installed that didn’t work well, consultants would stop specifying them, and dealers would stop pitching them to their customers.”

Cody Plagge is the project manager for Dimensional Communications, the Listen-certified integrator that installed the Riverview School District loop. He said he believes the experienced engineers at his firm could have figured out loop installations without the training. Still, Plagge said, Listen’s installer test kit has proved a valuable tool and the certification is a value-add when bidding for projects. “Certifications are always nice to have. Specs or consultants might call out for that in order to get a job, and we can comfortably write down that we’ve got that certification. It might have won us a job or two.”

While some installers may have complained about the certification process, he argues it’s unwise to take loop installations too lightly. As simple as the technology is at in its most basic application, installations aren’t always straightforward. Structural metal, for example, will interfere with and reduce the strength of the magnetic field. Existing electrical systems may interfere as well, creating electromagnetic background noise that produces an audible hum and reduces sound clarity.

Also, depending on where the loop is installed, it might require a more complex design than a simple perimeter loop. A space might require an array (a series of loops) to avoid structural metal, or a phased array, where two arrays are overlaid but offset to avoid dead zones. All this needs to be accounted for in producing a loop that conforms to the IEC standard, which establishes baseline measurements for magnetic field strength across a given space. “It seems like a simple thing,” Gennter said, “But if you treat it like a simple thing, you’ll get yourself in trouble. It has to be engineered.”

To help installation teams hit the mark the first time, Listen uses 3D modeling software. Installers provide Listen site plans, CAD renderings, and a clarification form with any other relevant information, such as the presence of metal elements and electrical equipment. Listen’s designers use that data to model the site, determining what kind of loop will be required and how much current it will need to meet the IEC standard. Whether installers use modeling software or not, doing a thorough site assessment is essential, because a successful installation makes life easier for the venue.

“There’s a little bit of fine tuning you have to do when you add it to a new area,” said Tom Ecklund, facilities director at Ford Airport in Grand Rapids, whose loops were installed by Hearing Loop Systems of Holland, MI. “But once that’s done it’s really a hands-off system.”

Right now, loop systems account for only a small percentage of ALS sales and installations. Listen’s Gentner puts the number somewhere between 5–10 percent. And while that may dismay loop advocates, for manufacturers, resellers and integrators, it means there’s immense potential for growth. “We’re talking about double-digit growth for quite a long time, because there’s no install base,” Gentner said. “If you took all the loop product and service sales, they’re going to be growing certainly more than 10% year over year.” Gentner estimates growth numbers could reach the 30–50% for the next several years, “because right now, there’s so little infrastructure.”

Still, he hastens to add, there’s no chance of loop making other ALS’s obsolete. Infrared, for example, allows secure transmissions, which loop can’t, while RF is substantially cheaper. “In many installations, loop is just cost prohibitive,” Gentner said. “For example, an NFL stadium can be covered with one RF transmitter at 260 MHz for a cost under $1,000. To loop a stadium, it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

A white paper authored by Griffitt suggests even the most basic installations will cost thousands of dollars, while estimates for larger-scale projects, like a large performing arts venue, run into the tens of thousands, upwards of $40,000 if the installation is complex. The loop installed in Greg Bawden’s Riverview School District boardroom cost $10,000, a figure steep enough that Bawden actually rescinded his original proposal and recommended a lower-cost RF unit. In the end, however, Bawden’s own confidence in loop’s superiority convinced the school superintendent that loop was worth investing in. “They stepped up and said, this is the right thing to do,” Bawden said. “And so far our experience has been positive.”

Similarly, Ecklund at Grand Rapids’s Ford Airport was undaunted by an initial installation that cost of $137,000. A second installation, to the tune of another $143,000, “was really a no-brainer for us,” Ecklund said, “because we had ample evidence that [the loop was] was received very, very well.”

Gentner believes that kind of recognition is turning the tide in favor of loop. “We are sensing a shift now,” he said, “in that people are putting in this type of technology not just because they’re required by the ADA, but because it delivers so much better an experience for the end user that it makes good business sense for the venue. In other words, they’re starting to put these systems in for the right reasons.”

Dave Zuckerman is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York.

The Gershwin Theater’s Got Rhythm

Broadway’s Gershwin Theater is providing a more immersive experience for its patrons by installing a hearing loop system from Listen Technologies. Bill Register, director of facilities and theater management for Nederlander, which operates the Gershwin Theater and eight other theaters in New York said, “The Gershwin Theater recently underwent a renovation with new seats and carpet. With the 10th anniversary of ‘Wicked’ upon us, we felt now was an opportune time to provide a different kind of upgrade to the theater. Being installed under the carpet, the hearing loop is invisible to the eyes, but for our patrons with hearing loss, the giant leap in clarity of sound is literally music to their ears.”

NEW AUDIO GEAR: QUICK HITS

Spotlight of New Sound Solutions

QSC Q-Sys

The next generation of QSC’s Q-Sys Enterprise Cores will be available in late Spring 2014. Doubling the processing capabilities of the models they supersede (Core 1000 and Core 3000), the new Core 1100 will provide up to 256x Q-LAN network audio Flex-channels, while the Core 3100 will provide up to 512x512 fixed Q-LAN network audio channels. In addition, QSC has also revealed that a software update, Q-Sys Designer 4.0, will also be available in early Spring 2014 to support both new and existing Q-Sys Cores. qsc.com/solutions/q-sys

Roland Systems Group’s VR-3EX

The VR-3EX is Roland’s new AV mixer that combines an all-in-one audio mixer, video mixer, touchscreen monitor, and USB port for streaming and recording. The unit advances the entry model, the Roland VR-3, by adding 4 HDMI inputs/outputs, built-in scaling with resolutions up to 1080p and WUXGA, HDCP support, full 18-channel digital audio mixer with effects, and over 200 video transitions and effects. www.rolandsystemsgroup.com

Atlas Sound TSD-HF11

Atlas Sound’s TSD-HF11 paging horn crossover and limiter is specifically designed for use with paging horns in applications where band pass filter and power limiting are required. The TSD-HF11 has a one input and one output configuration and includes input and output trim controls, selectable hi-pass and lo-pass filters, and a variable limiter to prevent excess signal from entering the amplifier. www.atlassound.com

Taiden/Media Vision HCS-1030U

With the HCS-1030U electronic nameplate, Taiden has taken another step toward achieving paperless meetings. Available as a standalone solution or as part of a conferencing system installation, the electronic nameplate can display information like the name and title of participants, the conference name/ logo, the company name/logo, the country name, and the participant’s seat. Meeting attendees see their information displayed electronically upon sign-in. www.mediavision-usa.com