If you’re a regular reader of SCN, then you’re familiar with the name Shen Milsom & Wilke, the New York-based consulting firm that holds an almost legendary status in the AV industry. The firm has no shortage of experts that we quote on an almost every-issue basis, and they all could have surely lent invaluable expertise on any topic in this issue. However, this being our special Audio Issue, we decided to try something a bit different. Rather than sit down with just any pair of representative experts, we decided to sit down with the firm’s founder, Fred Shen, and invite along one of the company’s most recent hires, the 24-year-old Alex Mayo. This, we thought, would provide unparalleled insight into how the industry has changed since its inception, and also provide an opportunity for two co-workers removed by generations to compare paths into the industry.

Fred Shen, left, and Alex Mayo, right.

SCN: Why don’t you both talk me through how you discovered an interest in audio and came to find yourself in this industry?

Fred Shen: It was 1969 when I arrived on the scene, working for an acoustical consulting firm, a very active, busy, sought-after consulting practice named Cerami and Associates. As an acoustical consultant, all the work we do is with architects, unlike some of our other disciplines, which are more on the engineering side.

I realized that sometimes when we were designing a space, particularly intricate, sophisticated, high-end, expensive spaces, we take painstaking care on the acoustic part of it. We do calculations and analysis—we had no computer modeling or anything like that in those days. Then at the same time, a different group, we’d call them sound system engineers, would then mount their loudspeakers and design their things, and then the inputs would be put into the architectural drawings. There was some coordination between sound system guys and acoustical guys, but if there was a problem at the end, it would always be, “Well, it’s his problem, he didn’t analyze it well, the loudspeakers are placed inappropriately.” The more important a space, the more this kind of conflict of opinion happened.

So as a young guy, I said, “Why don’t we hire some sound engineers into our firm and we can do this together. If things go wrong, there’s one single responsibility—it’s our problem, not his or theirs.” I had that in mind for a long time.

The visual side was nothing, because it was basically the Kodak 35mm slides that you drop into a slide projector. As late as 1992, when I went to Kuala Lumpur to present to the Malaysians about our services, I carried a slide carousel. As late as that! But anyway, going back a little bit, I always had in mind that we had to get sound systems and acoustics together. They have to go hand in hand. So I talked to my boss, Mr. Cerami, and he said “Freddy,” which nobody ever calls me except Vito, “Freddy, when you have things under your control you can do whatever you want. But as long as I’m in control I’m not interested.”

Fast forward to 1986 when we started SM&A (Shen, Milsom, and Associates). We immediately hired a part-time AV guy—we couldn't afford to pay full time. At that time we were starting to call it “AV” because there was an AV consulting firm called the Wilke Organization. It was the first-ever audiovisual consulting firm. Sound systems were probably 90 percent of their revenue. The “V” was basically slide projectors. No big deal.

Hubert Wilke and I had become friends when I became a partner over at Cerami, and he and I would get together to share leads, like co-marketing. And I even said to him “You know, we should get together, Cerami and Wilke.” But Cerami was not interested. Come 1986 when we had a partnership problem over at Cerami, and the non-compete agreement was null and void. We started this firm and got right into sound systems, and became probably the first, although there’s no proof of that, so, one of the first firms to have dual discipline.

SCN: At the time dual discipline was about 90 percent audio and 10 percent video?

FS: Yeah, that’s right. There was very little video. But when we started in January of 1986, a couple of months later IBM came out with the first personal computer, called the AT. And I bought one, because this is like the future. You could tell that peripherally there was some IT coming along, and some video appearing. A PC is basically a video screen, and all of a sudden the IT has to require the video display, and the forces were squeezing the two together to a point that the line between them was just blurring and then gone. And then we immediately got into IT, and that’s when we did that project [pointing to a poster of the Petronas Towers in Malaysia].

Alex Mayo: Picking up right from where he left off, in 1989 I was born. So you have been doing this for longer than I’ve been breathing.

For me it was mainly the typical story of being interested in stereos on a smaller scale, but academically when I got to college, I went to be trained as an acoustician at an acoustics program at the University of Hartford. I was looking for a major, because I knew I wanted to do something audio but I didn't want to work behind a mixing console as an audio recording engineer type of position, so I did a search when I was looking for schools, and there was an article in the Chicago Sun Times—I’m originally from Chicago—that had University of Hartford in the article, and mentioned an acoustics engineering program. And I just knew this was exactly what I’d been thinking of.

When I got there I still had that nagging desire for electronics, hardware, stereo systems, things like that. And acoustics is very theoretical—I did really enjoy that, but I didn't want to cut out the other side of it. So I actually met with the dean of the engineering school and we worked to design my own major, where we would take the musical and architectural courses and combine in some of the electronics courses as well as some of those audio recording engineer type courses.

Fast-forwarding toward the end of my schooling, I started looking for companies that did some type of work that I could use this major for, and SM&W was actually one of the companies on a list of maybe three or four—I knew I wanted to move to New York so that narrowed it down—and on the short list of places I could see myself at, this was definitely one of them. And it turned out perfect because just how Fred saw how sound systems and acoustics needed to come together, that's kind of what my position wound up being here—in the AV department but with an acoustics background, so able to keep the acoustics in mind when designing an audio system.

Video is a little more than 10 percent now, and that was probably the biggest part of catching up for me, because there was no part of my acoustics discipline that dealt with video. And it's a little more than a slide projector these days.

FS: For years when we were looking for new recruits in the AV field, we would grill the candidates far more on the ‘A’ side, because the audio engineering is quite complicated and sophisticated, and video is, when it comes down to it, much simpler. Because they’re visual and people want that visuality, the whole splash of images and motion images. Audio on the other hand, people hear and take for granted—they don’t even know why they’re hearing it. So when we test the qualification of the candidates, we’re more interested in their audio skills. Video they can pick up.

SCN: Talk to me a bit more about what drew you to audio and acoustics in the first place.

Left to right: Jim Merrill (current partner and board member), Fred Shen, and Dennis Milsom.

FS: I came here as a foreign student, and the aeronautical field was something that always fascinated me as a kid. That this big hunk of metal would actually go airborne—it just bugged the hell out of me. I would read cartoon books looking for airplanes and pictures of airplanes. So I majored in aeronautical engineering when I came [to the U.S.] not knowing that when I graduated—it was 1965, the peak of the Cold War—so America and Russia were building the best fighter jet airplanes and the longest range missiles and they were hiring ‘aeros’ left and right. My senior year, there were employment positions page after page after page, and all the defense contractors would be on campus recruiting—the likes of General Dynamics, NASA, Boeing, Lockheed—you name it, they were on campus offering the graduates employment. They can have their choice of geographic locations or the type of defense contract these companies have for the government. Whereas me, I’m a foreigner. I’m an alien, they called it. So they couldn’t touch me.

I basically drifted around—I actually received a deportation notice. “Mr. Shen, you have graduated with your BS, you are not employed where your practical training as a foreign student in your field of endeavor…” my field of endeavor wouldn’t hire me. So I drifted, I had to go to graduate school, came out to New York, went to NYU, still in the aeronautical/engineering field—I don't know why. But I needed a part-time job to pay for the expenses and my first part-time job was as an engineering apprentice at this firm called Mason Industries. They manufacture noise and vibration control products, so that’s how I learned about noise control, which is acoustics. I just kind of landed in it.

AM: I was very into analog type audio when I was younger. And the most advanced thing I had was a pretty nice CD player that my dad had. It was a setup with an amplifier, pre-amp, that kind of stuff. But when I started here, one of the biggest shocks—and it shouldn’t have been—was seeing how much was digital at this point. Everything from an analog standpoint, its only the end-point now. It’s the last part of the chain and the transport is all digital. So that was a bit of a shock, but it shouldn't have been since it was 2012.

But it seems like the biggest difference from when I originally had this idea of audio and stereo systems is that I guess I just assumed that a concert hall was just like a bigger version of my living room stereo. In some ways it is. But really getting into the digital transports—that’s been one of the biggest differences for me. From right on the cusp of the end of the analog days to kind of now everything is transported digitally—it's the convergence of IT.

FS: How long have you been with us now?

AM: A year and a half. This June will be my two-year anniversary.

FS: It feels like you’ve been here forever! Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

SCN:It must be a good thing.

FS: So a year and a half, and I can tell that he’s like a sponge. Just soaking up a lot of knowledge. So what is the most exciting audio system that you’ve ever been involved with? Which project?

AM: I would say between NYU Abu Dhabi and the Medina Convention Center, which was designed by me, Bill Nattress, and Rob Badenoch worked on that. Those were the two because I started on them from the beginning and was really able to see the design and performance come together.

FS: You just named two Middle Eastern projects. NYU Abu Dhabi is an amazing project. It’s a complete new campus of three or four million square feet with about seven or eight disciplines.

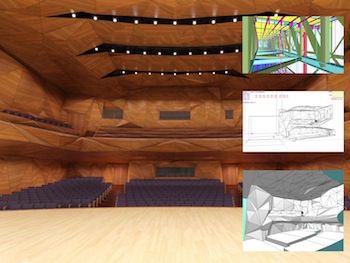

AM: There are a few quite large performing arts halls in NYU Abu Dhabi. I think the most interesting for me was to see—from a certain aspect I could immediately understand the analog side of it. You’ve got power amplifiers to line array loudspeakers, things like that. And also from being with Rob Badenoch, he had the 3D model and we were able to see the simulations and auralizations—all of that was really fascinating and started almost as soon as I started working here. And I was like, “Wow is this what it’s going to be like?” In fact during my interview when I first met with Steve [Emspak] I walked past Rob’s desk and he showed me the system he was working on.

FS: Today we can predict how the acoustics and the audio are coming together. In the old days we couldn’t. You would just do the best you can. And if it was a really large concert hall they would actually build scaled models and use a laser pointer to see the retracing.

AM: I never knew that.

SCN: What were some of the big eye-opening moments you encountered when you first started working here, and saw how things worked at a firm like this?

AM: One of my other backgrounds is in BIM and 3D Revit modeling, so I was aware from an electrical side of things that you could build something in 3D and work it out, but seeing EASE in use and the Bose modeler. I’d used that a bit in school, but it was always on a much smaller scale—maybe as large as a high school auditorium that we’d have a model of. So seeing that scaled up to a 2,500-person theater is amazing to see it still works.

Also, when I was at InfoComm I sat in on the FIRmaker for finite impulse response filters panel—there was a talk on that and a lot of DSP manufacturers now that are using these to work. The whole point is to now have a linear frequency response and you can really just paint the audience with the software, and with the power of DSPs it’s great that we can do this now. That’s one of the things that in my head I would have thought was possible, but it’s kind of new now. It’s a good tool for all designers—not just acoustics or AV. Everybody can think of audio as more than just placing a loudspeaker on a wall, and architects will also enjoy it because we can work around their constraints a lot better.

An example of the acoustical modeling the firm created for NYU Abu Dhabi.

FS: And even more importantly, sometimes on a design team, people have differences of opinion. So we say we should do this that way, we should place the speakers that way. And the architects will say, “No not really we don't want to see that there we don't want to do that there.” And if it really comes to a situation where some decision has to be made, we can actually simulate the quality of sound—option A is going to sound this way, and option B is going to sound that way. So we built a room here called our training and simulation room, with a lot of acoustical thick panels because we wanted the room to be totally non-directional. And we can use electronic sound systems—loudspeakers—and feed in the modeling information, and you will hear the future quality in that hall. So we can prove to the architects, if we do that it won’t sound so good.

SCN:What are some of the starkest examples of how things have changed since 1986?

FS: The physical model I mentioned as compared to electronic modeling. That is just a huge leap.

AM: Things like AVB, CobraNet, Dante—now you’re just using a building’s network to distribute audio throughout the whole space. Where I guess before you would just be running a ton of wire and cable.

FS: What you just said brought up another thought I had. With a digital audio distribution network versus analog, analog is basically zoned—zone one for east corridor northwest, first floor, zone two is this, etc. Now in the digital world, each single loudspeaker literally can be a zone in to itself. So picture in a large corporate or large hospital environment—the background music system can be used as a paging system, and if employees wear their access cards and the right chips are in the card, not only for access but for identifying their location, in a hospital when you’re paging and they say “Dr. Smith” and Dr. Smith is having a sandwich in the cafeteria, you need only to energize that one loudspeaker closest to him. So you don’t disturb the patients in all the wings and lounges. You just go right to the spot. That is amazing.

SCN: What are some of your more audacious predictions for the future?

AM: What I would like to see is, aside from improving processing power in DSPs, and I think they’ve pretty much figured out loudspeakers at this point, I'd like to see the design tools that are available come together a bit better. For instance, sometimes we’re using AutoCAD to do the sketch, we’re using Revit to deal with coordination, then we’re using EASE to do a preliminary acoustic model, maybe we’re using Bose modeler—it would be nice to see them come together into one thing. If EASE was a plugin for Revit, we’d all have access to some of these very high powered tools. Probably as computers get better, these are the types of things that will happen. It comes down to the same physics that [Fred] learned in school.

FS: The saying goes, you can’t defy the laws of physics. They’re the rules.

AM: Our schooling was not that much different from a raw engineering standpoint. And those physical principles will stay the same. But it would be nice to see these tools converge a little bit more. Hopefully they’ll have an app for that someday.

FS: We were brainstorming about apps the other day for SM&W, and I said how about an app on a smartphone that you can actually produce the sound of an auralization—the simulated sound, predict the quality of the future. If you had that, you could be sitting in the conference room with the design team and say, “Let me show you what it sounds like.”

AM: We might be a year or so away from that… From a manufacturer standpoint, it seems like there are a lot of products out there. Some seem to be relics from the past that just seem to have a digital makeover. And the reason I say that is that I really truthfully don’t see a purpose for them. Some of the ideas behind matrix switching and HDBaseT are great tools for us to use in digital transport—it’s probably one of the best—but some of the implementations of it almost seem like its just a refresh of an old analog style, so I guess something that’s more revolutionary in the digital age… I guess if I could answer that I’d probably work in manufacturing.

Chuck Ansbacher is the managing editor of SCN.