This is Part 1 of a three-part interview. Part 2 |Part 3

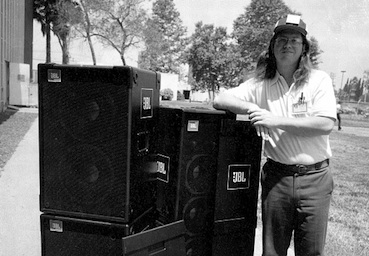

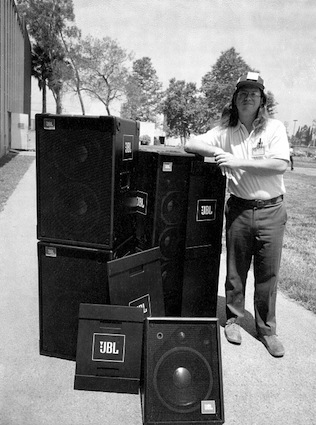

There are tales of longevity in the pro audio industry, and then there are epics. Beginning in 1976, Mark Gander joined the JBL crusade as a transducer engineer, and since that time he has made a journey through various roles in engineering, product development, and marketing.

“That's old school, last millennium, which I can say being a company man that’s worked through both,” Gander muses.

Now he has been named to a position that merges his various roles from the past into what sounds like a very new-millennium post: Director of JBL Technology. That sounds like the title that the CEO of a new startup would don on his engineering guy, and that’s probably apt, since Gander will be focused on the very high-minded ideals of intellectual property portfolio management and technology development.

Here his longevity at the company, with a side gig as the JBL historian and keeper of technological artifacts, comes in handy. “JBL has always been a technology-based company, pushing the envelope in terms of what new materials, methods, or concepts are available or we can create that make loudspeakers better and provide better solutions for our customers,” Gander observed.

What follows is a transcription of my conversation with Gander about the past, present, and future of his contribution to JBL Professional and Harman Professional family of brands.

SCN: Director of Technology sounds like a very futuristic title. What does it entail?

Mark Gander: The Intellectual Property, the patents and trademark, that's the protecting part of it. And then, technology development is being engaged with the engineers within JBL Pro, and expanding into interfacing with the broader Harman Professional and also Harman’s automotive and consumer products divisions. Beyond that, it’s monitoring the overall marketplace and world in terms of what technologies are being developed and are available, and how can we adapt those in unique ways that provide the newest and best solutions for acoustic problems and loudspeakers and sound systems.

SCN: As JBL’s resident historian, what innovations would you say have contributed to the intellectual property portfolio over the decades since the company was founded in 1946?

MG: I think not only myself, but all the engineers at JBL are aware of the heritage and lineage of JBL going back to the founder, James B. Lansing. Early on, he brought new magnets called AlNicCo—Aluminum, Nickel, and Cobalt—and adapted them to loudspeakers to improve their performance. He made note of a new method of flattening wire, and implemented the use of flat-wire voice coils instead of round-wire voice coils to get more coil and turns density in the magnetic gap and make more efficient loudspeakers.

It was those and other uses of new materials, and developing new methodologies and applying them in new products, that brought very significant and signature products to JBL very early on. For instance, the D130 15-inch full-range loudspeaker, which was a Hi-Fi speaker but it was adapted by Leo Fender for Fender guitar amps. It was also used in the PA system at Woodstock. We have continued to do that all through the 37 years that I’ve been at the company.

SCN: What are some of the other highlights from JBL’s product history?

MG: JBL has the advantage of being in Southern California, which is home to not only the movie business and recording business when it exploded in the 1960s, but also the aerospace industry. So when titanium was able to be made into a thin foil, we were the first ones to adapt that and make titanium diaphragms for tweeters and compression drivers, which are ubiquitous now throughout all loudspeakers in consumer and pro applications.

In the 1990s, the EON sound system is one of the most dramatic examples, because it’s not just a transducer, like a D130 or a titanium diaphragm compression driver, it’s a completely integrated sound system, where we were the first ones to do a molded enclosure powered system with electronic crossover, bi-amplification, and a basic mixer, all integrated into a single packaged powered system, and I think it’s fair to say the EON created a revolution in the portable PA market and in the package PA market, not just for musicians but all applications.

We’ve had a number of patented developments like the Differential-Drive dual-coil low-frequency drivers, the titanium diaphragm, and the thermal management systems in EON, but ultimately the technology is always in the service of the customer. I’m fond of saying that the customers are looking to get their message out, and the sound system is actually a necessary evil. If they could just stand in front of a crowd and play their music or give their speech and everybody could hear and understand them, there’d be no need for a sound system. But that’s not what the physics and the reality are. So by making the process as simple as possible, by bringing to bear these technologies and methods, and by integrating them in unique ways, you come up with something that brings good sound and communications capabilities to as many people as possible and as many end-users as possible.

SCN: What else does the intellectual property part of your new role entail?

Kirsten Nelson is the editor of Systems Contractor News.