One Friday morning in March, in front of twenty or so amazed onlookers, a two-foot-tall humanoid robot named Eve lurched, arms swinging, into Michael Jackson’s Thriller dance, then after a pause, gracefully performed tai chi. The room erupted in applause. The witnesses to Eve’s performance were educators—teachers, administrators, and IT staff—who had joined hundreds of their colleagues on the campus of New Jersey City University (NJCU) for the NJEDge Faculty Showcase, an annual event featuring trends and best practices in educational technology.

While they clearly made an impression on those in the room, Eve’s slick moves weren’t nearly as audacious as what had preceded them. For the better part of the session, presenters Dr. Laura Zieger, a professor and Chairperson of the Educational Technology Department at NJCU, and Sofia Levchak, a doctoral candidate, had followed through on the promise of its title: “Humanoid Robots in the Literacy Curriculum.” They had attempted to explain how a dancing robot could help teach students to read.

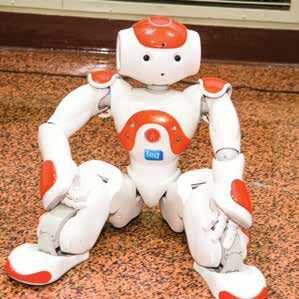

THE FUTURE IS NAO?

Researchers are exploring how new technologies & tools, such as NAO, can help improve student literacy. The robot in question is a NAO, one of three models produced by the French firm Aldebaran. With a diminutive stature, rounded features and childlike voice designed to engage, the robot is gaining traction as a teaching tool. And while the programming the robot requires points to its use in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) education, a small body of research suggests humanoid robots could actually be used to improve literacy. In one study Levchak cited, students in Japan increased their English vocabulary at a greater rate when attempting to teach a lesson to a NAO than when observing a teacher. In Madrid, students programmed two NAO machines to perform a scene from Hamlet. The idea, Levchak explained, was that students first had to understand the language of the scene before they could program text-appropriate motions in the robots.

For Levchak and Zieger, NAO as a literacy tool is anything but a novelty. In fact, it’s the subject of Levchak’s dissertation. A reading intervention specialist, Levchak is also in the second year of NJCU’s emergent educational technology leadership doctorate program. Although her thesis is still taking shape, she hopes to assess NAO’s utility in an ESL setting. Levchak herself admits she had doubts about NAO before she delved into the research.

Members of NJCU’s Educational Technology Department (left-right): Dr. Leonid Rabinovich; Dr. Cordelia Twomey, Dr. Laura Zieger, Chairperson; Dr. Christopher Shamburg; Giulio Dininno, Dr. Christopher Carnahan. “I was really skeptical at first,” Levchak said. “Okay, a few songs and dances, but how is it really going to be a tool? But then so many ideas started coming to mind, like that study in Japan—the kids were teaching the robot, and because they were teaching it, they were learning through it. So it’s a great tool, you just have to know how to approach it.”

- According to Dr. Christopher Carnahan, a professor and coordinator of the doctoral program in Educational Technology Leadership at NJCU, “The NAO has a low barrier entry to have students learning content knowledge while incidentally learning stem initiatives such as programming and robotics. I am often asked what can the robots do. My response is always ‘anything that you want and can program’.”

Zieger, who chairs NJCU’s ed tech department and helped create the doctorate program, won’t mind if her protégé’s work at first raises eyebrows. Innovation, she says, is a key component of the Jersey City school’s program.

“What we try to do is open it up to students to see that first you survey the field, you understand what other people have learned, you gain that knowledge and experience, and then you apply what you know and innovate so you can bring something new to it.”

NJCU’s Rossey Hall in Jersey City, NJ. LOOKING AHEAD, BUT ROOTED

Dr. Christopher Shamburg, an ed tech professor and doctoral program coordinator at NJCU, stresses that, although innovation is a priority, the NJCU program keeps its students grounded in reality. Theories of learning constitute a vital foundation and new tools and technologies are exciting, he says, but educational technology is primarily about education, not novelty for its own sake. A high school English teacher for ten years before entering academia, Shamburg knows all too well that “it’s about more than just dropping a new computer or a certain technology into a classroom” and expecting magic to happen. For some of the program’s graduates, who hope to go on to leadership roles as administrators in K–12 or higher education environments, understanding the real world implications of implementing a new technology will be vital. So while Shamburg and his colleagues hope to foster a generation of innovative thought leaders, NJCU’s EdD candidates need to keep “one foot in practice and what’s going on in the real world.”

“We really try to look at this as an ecosystem approach,” Shamburg says. “How will that technology fit into the ecosystem of the school? What are the training and professional development needs? What infrastructure is required? What’s the curriculum? What do the students need?” Extending the analogy, Shamburg says new technologies are akin to an invasive species. The invader might seamlessly integrate and thrive in its new environment, or it might die off quickly. Worse yet, it might cause wide-ranging disruptions. New technologies, similarly, can eat up valuable classroom time in set up and troubleshooting or place additional strains on over-burdened teachers, all without necessarily adding value. Worse still, they may distract students, engaging them in disruptive ways.

“It’s about effective use of technology. You really have to consider both the intended and the unintended consequences,” Shamburg says, adding, “we’re not technology salesmen. Everyone has to have a healthy skepticism at times.”

Because budget is a primary concern for so many educators, Shamburg says he tries to promote affordable technologies. One of NJCU’s graduate courses, called Authoring Tools, explores DIY approaches to digital media using cheap or free software and athand technologies.

“You could probably get through that entire course with your computer’s microphone,” he says.

E-textiles are one of the emerging ed tech trends Shamburg favors precisely because of their accessibility. Combining newly affordable materials like conductive thread and flexible circuit boards with the contents of a sewing kit, e-textiles allow children to sew basic circuits and sensors into clothing, creating wearable technology.

“It’s very STEM-oriented,” Shamburg says, “but it also has a craft element; it’s very artisan. And it’s really eye-opening for the kids.”

NJCU’s ed tech department runs a wearable technology pilot program, working with educators around New Jersey to figure out how e-textiles can be used effectively in K-12 and college classrooms. This kind of fieldwork, Shamburg notes, is part and parcel with keeping ed tech doctoral candidates grounded in the day-to-day realities of education.

“We’re very involved in making new things happen,” he says, citing other programs like a partnership with Jersey City’s A. Harry Moore School to promote the use of DIY and accessible technologies in special needs classes. “We have these partnerships with schools and districts and organizations where we’re not only figuring out what the rules are but making them as we go.”

COMMUNITY OF LEARNERS

For some of the program’s doctoral candidates, making the rules can be an intimidating prospect. Levchak admitted to feeling somewhat exposed by the degree to which NJCU’s program is advanced in the field.

“It’s a double-edged sword, because there’s not a lot of research out there,” she says. “At least we know that whatever study we conduct is going to be adding to that body of research.”

If doctoral candidates feel exposed or isolated, Zieger says, that’s by design. The NJCU program is conducted primarily online. Candidates are only required on campus for one week each year. It may seem counterintuitive given the hands-on nature of the material, but Zieger says the 51:1 schedule has specific goals. One is that the program’s participants get to experience first-hand the isolation attendant to online learning. Graduates who go on to work in online or distance-learning environments will have learned exactly what kind of support online students require to overcome their isolation. She knows, having earned her own EdD at California’s Pepperdine University. Though that program requires more face-to-face time than NJCU’s, Zieger says, it includes extended periods of distance learning—enough to give her great insight into the experience.

Members of NJCU’s Educational Technology doctoral program preparing for leadership roles. “You have to build into your program a sense of community and a sense of belonging and interaction and particularly feedback,” Zieger says. To that end, NJCU’s program is cohort based. Candidates enter each year in groups of twenty. They meet online before being thrown together in their first oncampus week for an intensive session of course work and group projects.

“You’re forced to work on a project with people you’ve never met,” says Amy Arsiwala, a member, with Levchak of the 2013 cohort. “You don’t know their personalities, or their capabilities.”

The experience, Arsiwala and Levchak agree, forges strong bonds among cohort members that carry through once the week ends. From that point on, students are conducting research and completing coursework independently, but they’re not alone.

“You’re really doing it asynchronously, but what we’ve managed to do is to create this community through the use of additional tools,” says Deborah Nagler, who entered the program with the 2014 cohort. “We use a lot of social networking, and social media. We’re in touch, sometimes daily, sometimes hourly, as a support group and to enhance [our work]. So we don’t feel like we’re out of touch. We feel very connected.”

In addition to the required one week on campus, NJCU faculty offer regular meet-ups on campus to introduce new technologies to the students. Attendance is optional, which puts the onus on students to take shape the course of their own learning, Levchak says.

“The professors put it out there. They say: this is what we have—who’s interested? Students have to figure out what they want to work with.”

The hope, Shamburg says, is that forcing students to work in relative isolation and seek out their own support will foster the independence they’ll need when they finish the program and step into leadership roles.

According to Arsiwala, it’s working. “It gives us the confidence that we can figure this stuff out on our own,” she says.

David Zuckerman is a Brooklyn, NY-based writer and frequent contributor to AV Technology magazine.

STAYING AGILE IN AN EVER-CHANGING DISCIPLINE

“While the adoption of new technology is intuitive to students, the adaptation of new technologies to be used as educational tools or resources is a challenge for instructors. Modifying current pedagogy, whether lecture-based, active or hands on, to meld seamlessly and synergistically with innovative technologies is time-consuming and can be resource draining. Programs like this one at NJCU are a necessary progression to pulling together an effective team that is skilled in creating a successful, technologically rich learning environment, and designing complementary instruction methods. Continual re-thinking as technology changes allows these doctoral students that ability to see education in a constantly morphing form rather than a fixed method, offering incoming students learning that is tailored to engagement and success.”

—Gina Sansivero, Director of Business Development, Education at FSR (www.fsr.education)