Rick Carlson (right) poses with Gregg Gronowski in front of 2/3 of their complete audio setup for G&R Sound around 1974-75. The rig was purchased from Heil Sound, who used it for The Who's 1973 tour.

Legend has it that the Beatles played Shea Stadium in New York City on August 15, 1965 through a Shure Vocal Master P.A. Shure didn’t introduce the Vocal Master until 1967, but whatever brand of vocal column speakers the Fab Four used that night, apparently supplemented by the in-house public address system, 50 years later we would know was woefully inadequate.

The popularity of the Beatles and other contemporary rock ‘n’ roll artists ushered in the era of amplified music, with performance venues mushrooming nationwide. Manufacturers had already begun to produce more powerful backline amplification, also branching out into mixer-amplifiers—such as the Vocal Master—for P.A. use, and as the new clubs sprang up, they sometimes provided a test bed for the emerging larger-scale products.

Of course, live music venues were nothing new. In the Los Angeles area, for example, the Hollywood Bowl had opened in 1922. On a smaller scale, the Whiskey a Go Go, in West Hollywood, opened in January 1964, barely a mile from The Troubadour, in operation since 1957. The former was inspired by the Whiskey à Go-Go nightclub in Paris, France, the first venue—opening in 1947—intended specifically for the playback of recorded music, popularizing the word “disco,” from its French description, “discothèque.”

Any number of U.S. cities boasted jazz and folk clubs, classical music halls, and theaters, but they largely relied on natural acoustics with little amplification. Making the vocals audible above the roar of a rock ‘n’ roll band playing through Marshall and Vox amplifiers generating 100W or more was going to require new P.A. technology.

While various individuals and companies were simultaneously working on developing bigger and louder speaker systems across the country, and around the world, particularly in the U.K., the birth of the modern concert production sound system can arguably be traced to a singular event. On February 2, 1970, the Grateful Dead arrived in St. Louis, MO to perform at the Fox Theatre, reportedly the second largest movie theater in the country when it was built in 1929. But with upward of 5,000 fans expected, the band had a problem—engineer Owsley “Bear” Stanley had been detained by police, along with the truck hauling the Dead’s P.A.

“There’s a phone call from the stage manager at the Fox. He says, ‘You still got those big speakers?’ He said, ‘Talk to this guy,’ and handed the phone to [Grateful Dead guitarist] Jerry Garcia,” recalled Bob Heil, now perhaps better known as the founder of Heil Microphones.

In 1957 the Fox had hired a teenage Heil to play the venue’s pipe organ. Visiting the venue a decade later he spotted four Altec Lansing A-4 Voice of the Theatre speaker cabinets being thrown out and took them back to his music store (one of the country’s first pro audio retail outlets) in Marissa, IL, 50 miles outside St. Louis. Recognizing that most P.A. systems were still too underpowered for rock ‘n’ roll, Heil used the A-4s as the basis for a massive rig, fabricating his own speaker cabinets and fiberglass horns, and powering the system with McIntosh hi-fi amplifiers.

A licensed ham radio operator since 1956, Heil knew his way around a soldering iron and was an inveterate tinkerer. He ran into guitarist Joe Walsh, then fronting the James Gang, and discovered they were ham radio buddies, and with Walsh’s encouragement, he grew the sound system (they still collaborate). Along the way, Heil developed one of the first electronic crossovers and a modular mixing console, subsequently replacing it with a Langevin recording console modified for live use by a recent graduate from the University of Illinois, Tomlinson Holman, who later developed the Lucasfilm THX sound system.

“That was the board we used that night [at the Fox Theatre],” he said. “I think that’s what blew them all away; we had these fabulous, wonderful things.” The Grateful Dead hired Heil for the remainder of the tour, and Heil Sound went on to work with Jeff Beck, ZZ Top, Humble Pie and many others.

Heil estimates that the rig at the Fox that night was capable of delivering over 20,000 watts. As a comparison, The Who, self-described “loudest band in the world,” put together a system of WEM columns for the 1970 Isle of Wight festival—attended by several hundred thousand fans—that generated just 5,000 watts. When the band arrived in the U.S. in 1971 for the Who’s Next tour they contacted Heil, and continued to use Heil Sound rigs on both sides of the Atlantic through 1975.

U.S. music venues proliferated through the 1970s and into the ‘80s, with New York City as the epicenter. “Club life is jumping, sometimes literally, because more and more clubs are geared for dancing instead of listening,” wrote John Rockwell in The New York Times of August 8, 1980, also noting the recent emergence of “dance-rock.”

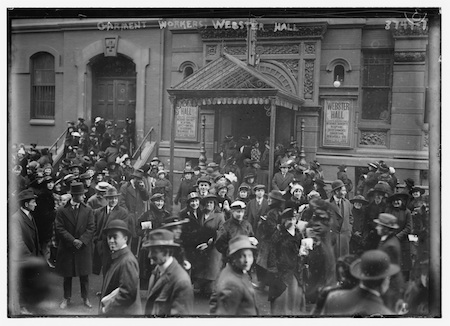

Garment workers outside of New York City's Webster Hall, 1915-1920.

The notorious Studio 54 had closed by 1980, but Xenon, the Electric Circus, and Bond International Casino—where the Clash famously played 17 shows in 1981—were keeping the flame alive as “the flashiest, most impressive discos of this kind right now,” Rockwell wrote. Indeed, the apotheosis of the dance club sound system was also in New York City, at the Paradise Garage, which opened in 1978 and occasionally hosted live performances. That now legendary system was developed by DJ Larry Levan in collaboration with Richard Long and Associates and Alan Fierstein of Acoustilog, who designed the acoustics and built custom electronics to both calibrate and creatively manipulate the sound. The system reportedly won every Best Disco Sound System award presented at Billboard’s annual International Disco Forum.

Rockwell also singled out Hurrah in Manhattan, which “can claim credit for originating the whole rock-disco craze,” and where “the sound system and dance space are first-rate.” There were also hard rock clubs, he noted, including the Bottom Line and the Other End, and folk, blues, and country venues such as Folk City, Tramps, and the Lone Star Café.

The tour itineraries for 1981 through 1983 for my own band—Medium Medium, a Nottingham, England-based “dance-rock” quartet—offers a further sample of some of the live music clubs of the era: Brooklyn Zoo, Danceteria, Irving Plaza, Mudd Club, The Peppermint Lounge, and The Ritz (later renamed Webster Hall), in New York City; 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C.; East Side Club, Philadelphia; in New Jersey, City Gardens in Trenton, Hitsville in Passaic, and Meadowbrook in Cedar Grove; Paradise Club, Spit, and Storyville in Boston; Clutch Cargo’s and Traxx in Detroit; Metro and Misfits in Chicago; 1st Avenue, Minneapolis; Merlyn’s, in Madison, WI.

Vinnie Macri, now product marketing manager for Clear-Com, was immersed in the New York club scene at the time, working for live sound specialist Quantum Audio, which supplied Clair Bros., Britannia Row, and other regional clients. “There wasn’t a lot of technology back then,” said Macri. “That’s when you tried stuff that you’d never tried before. It was all experimentation; you were trying different things only to try and make it sound better.”

All the Manhattan clubs came to Quantum for equipment. “When the PM2000 came out [in 1978] Quantum had a Yamaha day at Irving Plaza; it was just down the block from us. The Ritz bought a PM2000 from Maryland Sound, who had put the P.A. in there.”

When Max’s Kansas City opened, Steve Bondy, who designed, installed, owned, and operated numerous club systems in the city, installed his P.A. “He bought a lot of stuff from us,” said Macri. “The Mudd Club bought everything from Quantum. They had a Martin Audio bass bin, a [Martin MH212] ‘Philishave’ mid-range box that later got changed to an EAW, a two-inch, and a one-inch, and a Tapco 12-channel console. I wound up babysitting that system for years.”

He continued, “From a technology point of view, in the ‘70s, it was all stacked P.A. Tramps had EAW full-range cabinets. They had an 18-inch [driver], a 12-inch, a 10-inch and a horn. You hung them up and that was the P.A. Maybe you bi-amped or tri-amped them.”

Not every system sounded good: “At CBGB’s, the 2-inch horn was aimed directly into a beam. It was the most horrible sounding room in the city.”

Then, one day, said Macri, “These guys in suits came in. They told us they’d bought a CBS theater on 54th Street and they were making a dance club. We gave them Richard Long’s business card; he went on to fame as THE disco installer.” That theater became Studio 54.

Macri eventually went into partnership with TD Audio in New Jersey, which built speaker cabinets, and also worked with Jim Toth, who was the sound engineer at the Peppermint Lounge, Hurrah, and Danceteria. “TD Audio built all the cabinets for the Pep and for Danceteria. It was around that time that you started to see integrated boxes: a low, mid, and high in a box, like the Clair S4. But for the high-end clubs those were all custom made—and we made them all.”

Steve Harvey (sharvey.prosound@gmail.com) has been west coast editor for Pro Sound News since 2000 and also contributes to TV Technology, Pro Audio Review, and other NewBay titles. He has over 30 years of hands-on experience with a wide range of audio production technologies.